Investing in China: Navigating Risks and Uncovering Opportunities

Navigating the intersection of tradition, modernity, and regulation in China’s dynamic economy

Introduction

Investing in China offers a blend of opportunities and challenges. As a country that bridges its ancient traditions with cutting-edge innovation, China’s rapid economic rise has transformed it into a global powerhouse. This growth comes with complexities, ranging from geopolitical tensions to evolving regulatory frameworks.

Cities like Shenzhen exemplify modernization and innovation, while historical centers such as Xi’an reveal the deep integration of new technologies like mobile payments. This progress is matched by a string of regulatory reforms targeting financial stability, monopolistic practices, labor malpractice, and corporate transparency. While these reforms have caused market volatility, they also underscore China’s long-term commitment to societal progress and sustainable growth.

For the level-headed investor, navigating these risks is essential. Despite the challenges, high-quality Chinese companies trade at significantly lower valuations than their Western peers, offering substantial potential for long-term gains. As is particularly evident in China, the goal to me is not to avoid risk but to ensure I am rewarded for taking it.

The Rise of the World’s Second Largest Economy

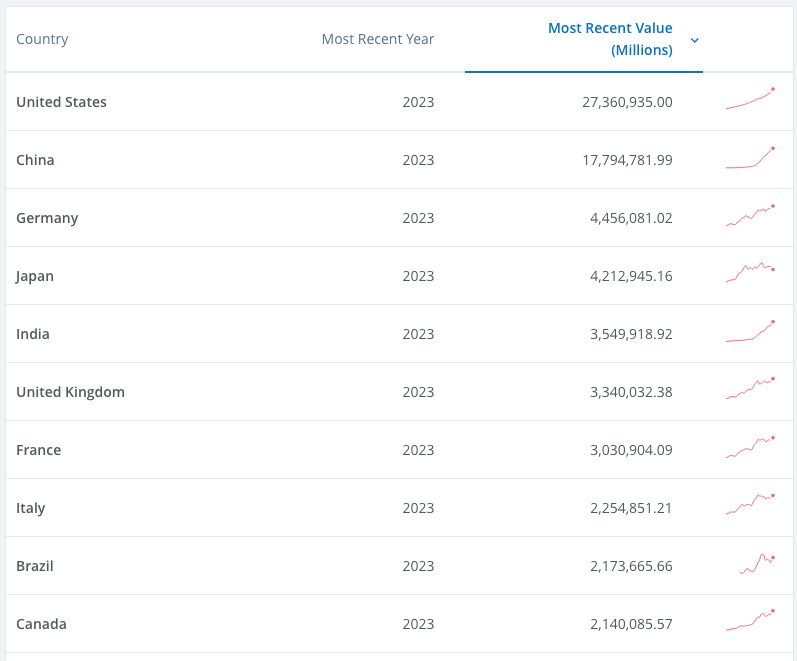

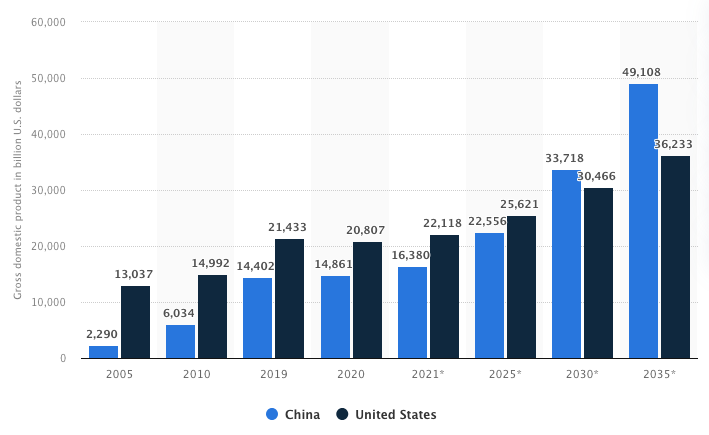

Prior to 1978, China was relatively isolated economically, following a strict central-planning model under Mao Zedong. China’s transformation began in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping introduced a series of market-oriented reforms under the policy of Reform and Opening Up1. These reforms marked the beginning of China’s transformation from an isolated, inward-looking country into the world’s second-largest economy; according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2010, China had overtaken Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy by nominal GDP2, after the U.S.

Between 2005 and 2020, the GDP of China grew from 2.3 trillion to 14.9 trillion U.S. dollars. During the same time period the GDP of the United States grew from 13 trillion to 20.8 trillion dollars. It is estimated that, by 2030, China will overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, with a GDP of 33.7 trillion dollars, compared to 30.5 trillion dollars.

Reform and Opening Up

The reforms from the late 1970s consisted in allowing private businesses, encouraging foreign direct investment, and liberalizing trade. However, China maintains to this day significant state control over key industries such as finance, telecommunications, and energy. This hybrid system is often referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics. China’s unique approach to state capitalism has allowed the country to grow its GDP 9% a year and has lifted over 800 millions of its citizens out of poverty3. This is perhaps one of the most notable achievements in modern economic history. The creation of Special Economic Zones4 (SEZ), like the one I experienced in Shenzhen, played a critical role in this growth, by encouraging foreign investment and allowing Chinese enterprises to innovate within global frameworks.

Shenzhen: From Fishing Village to Global Tech Hub

When I visited Shenzhen in 2014, the city was already booming as China’s technological and manufacturing hub.

Located in southern mainland China off the border with Hong Kong, the city has a remarkable transformation story. Originally a small fishing village, it began its modern ascent in 1980 when it was designated as China’s first SEZ. This move was part of China’s broader economic reforms aimed at opening up the country to foreign investment and market-driven practices. Shenzhen’s SEZ status allowed it to experiment with capitalist-style economic policies, which spurred rapid industrialization, technological development, and urbanization. Its proximity to Hong Kong made it a natural hub for foreign investment, trade, and manufacturing.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Shenzhen became a global manufacturing center, producing electronics and consumer goods for companies worldwide. It is also home to major Chinese technology companies like Huawei and Tencent.

Today, Shenzhen is one of China’s wealthiest cities, known for its cutting-edge industries, vibrant economy, and as a symbol of China’s rapid economic rise. Its population has skyrocketed from around 30,000 in the 1970s to over 12 million today.

The speed at which China modernized its cities and industries feels remarkable to me, especially when I compare it to the more traditional, historical city of Xi’an.

Xi’an: The Intersection of Tradition and Modernization

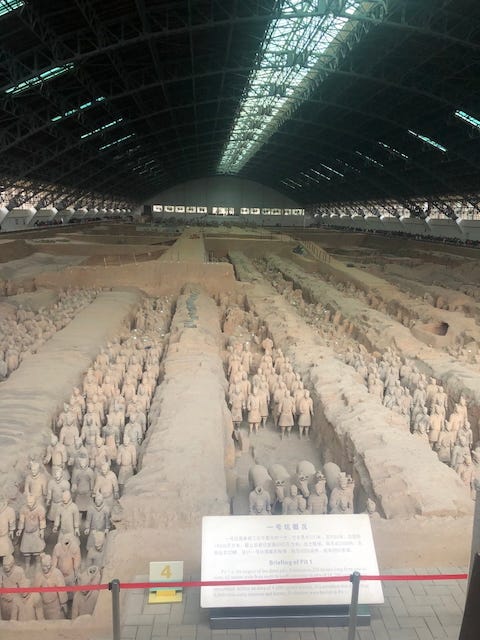

In 2019, when I traveled to Xi’an, I noticed how China had moved beyond its industrial boom toward a more sophisticated digital economy. Xi’an is a city steeped in history, home to the Terracotta Warriors and centuries-old monuments.

Yet, on every corner, it was clear that China’s ancient traditions were now coexisting with a high-tech present. Most striking to me was the shift to mobile payments. Instead of cash, QR codes and mobile apps like WeChat Pay and Alipay were accepted everywhere. My Western debit and credit cards were not accepted for signup on these platforms, and paying with cash or cards was not an option. As a result, I had to purchase dedicated prepaid cards from kiosks around the city. This was a clear sign of China’s embrace of the digital future, leapfrogging Western economies in terms of digital payment infrastructure. This shift exemplifies a broader trend in China: the country’s ability to innovate at scale and rapidly adopt new technologies.

Why Invest in China?

China is a unique and captivating investment destination due to several key factors: its sheer size, its increasing global importance, and the distinctiveness of its corporate landscape. With a population of over 1.4 billion5, it is five times larger than the U.S., and what transpires within China’s borders now has a ripple effect across the world. What sets China apart, however, is that its most influential corporations are homegrown and operate under a business model quite distinct from Western companies. Charlie Munger during an interview in 2021 praised China’s economy strategy and he once said on China:

“[…] the reason that I invested in China is I could get so much more, so much better companies at so much lower prices and I was willing to take a little political risk to get them.”

China’s Infrastructure Boom

China’s rapid development over the last decades is unparalleled, with infrastructure that outpaces many of the world’s leading cities. Major metropolitan areas, such as Beijing and Shanghai, boast transportation systems, like high-speed rail, that leave Western equivalents far behind.

However, much of the country continues to undergo significant development. Cities like Beijing and Shenzhen have modernized, while others smaller cities and large rural regions are now beginning to catch up. This continuous development process suggests that China’s growth still has significant room to expand, both economically and infrastructurally.

Dynamic and Ever-Changing Landscape

China’s corporate environment is intensely dynamic. Once dominant companies are constantly challenged by emerging competitors and sometimes overshadowed, some of which did not even exist a decade ago. In stark contrast to the West, where companies like Amazon and Google remain unchallenged, the Chinese market exemplifies creative destruction on a scale that is both invigorating and humbling.

Chinese companies are not just fast adopters; they are often at the cutting edge of innovation. For instance, I experienced firsthand how mobile payments have been commonplace in China years before similar technologies took root in the West. Young and innovative businesses, once small and considered marginal, like Shein6 in the fast-fashion retail sector and Pinduoduo7 in the e-commerce sector have pioneered Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M) model and social commerce that redefine how consumers shop online. Furthermore, Pinduoduo has focused on rural and lower-tier markets that gave it an edge that competitors initially overlooked. These companies have challenged and taken market share from e-commerce giants such as Alibaba8 and JD.com9. Similarly, companies like Tencent10, which pioneered revenue models based on virtual goods long before competitors worldwide followed suit, demonstrate how China often offers a glimpse into broader global trends.

China’s Integration With the Global Economy

China’s rise as a global economic powerhouse has deeply intertwined its economy with that of the rest of the world. This inter-dependency is not only a result of China’s massive growth in manufacturing and export capacity but also its significant role as a consumer of global goods, its integration into international supply chains, and its technological advancements. Many multinational corporations, such as Apple, rely heavily on China’s manufacturing infrastructure. For instance, approximately 70% of Apple’s iPhones are assembled in China, highlighting the critical nature of China’s role in global production. Disruptions in China, whether due to regulatory changes, geopolitical tensions, or health crises, can send shockwaves through international supply chains, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic when lockdowns in China caused delays and shortages worldwide.

Technological Interdependence

The technological sector is another domain where China’s global interconnection is profound. China is not just a key player in manufacturing hardware but is also at the forefront of developing technologies in 5G and electric vehicles (EVs). Chinese companies like Huawei11 and BYD12 are leaders in their respective fields, and their innovations influence global markets.

The production of semiconductors and microchips in Taiwan, a critical hub in the global supply chain, is essential for industries ranging from consumer electronics to automotive. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company13, the world’s largest contract chip-maker, dominates the semiconductor manufacturing market, producing the advanced chips used in everything from smartphones to electric vehicles. Any disruption in Taiwan, whether due to geopolitical tensions or natural disasters, could have severe repercussions for industries and companies globally. These risks are heightened by the geopolitical tensions between China and Taiwan. China views Taiwan as a breakaway province, and any conflict or escalation between the two could disrupt the semiconductor supply chain, with far-reaching consequences. The U.S. has increased its involvement in this area, both in terms of diplomatic support for Taiwan and legislative efforts to reduce dependence on foreign semiconductors. The CHIPS and Science Act14 in the U.S., passed in 2022, aims to incentivize semiconductor companies to establish factories on U.S. soil, promoting domestic production and reducing reliance on Asia, especially Taiwan, for these critical components.

Economic Inter-dependencies in Western Markets

Western businesses are highly dependent on China not just for manufacturing but also as a significant consumer market. Western companies such as Apple, Nike, and Starbucks derive substantial revenue from China’s vast and growing middle class. For instance, Apple generates about 19% of its revenue from China15, underscoring how crucial the Chinese market is to its global operations. The risk of investing in China, therefore, is not confined to Chinese companies alone but extends to Western businesses deeply intertwined with the country’s economy. Any economic confrontation or decoupling would have significant consequences, potentially disrupting global supply chains, production, and market demand.

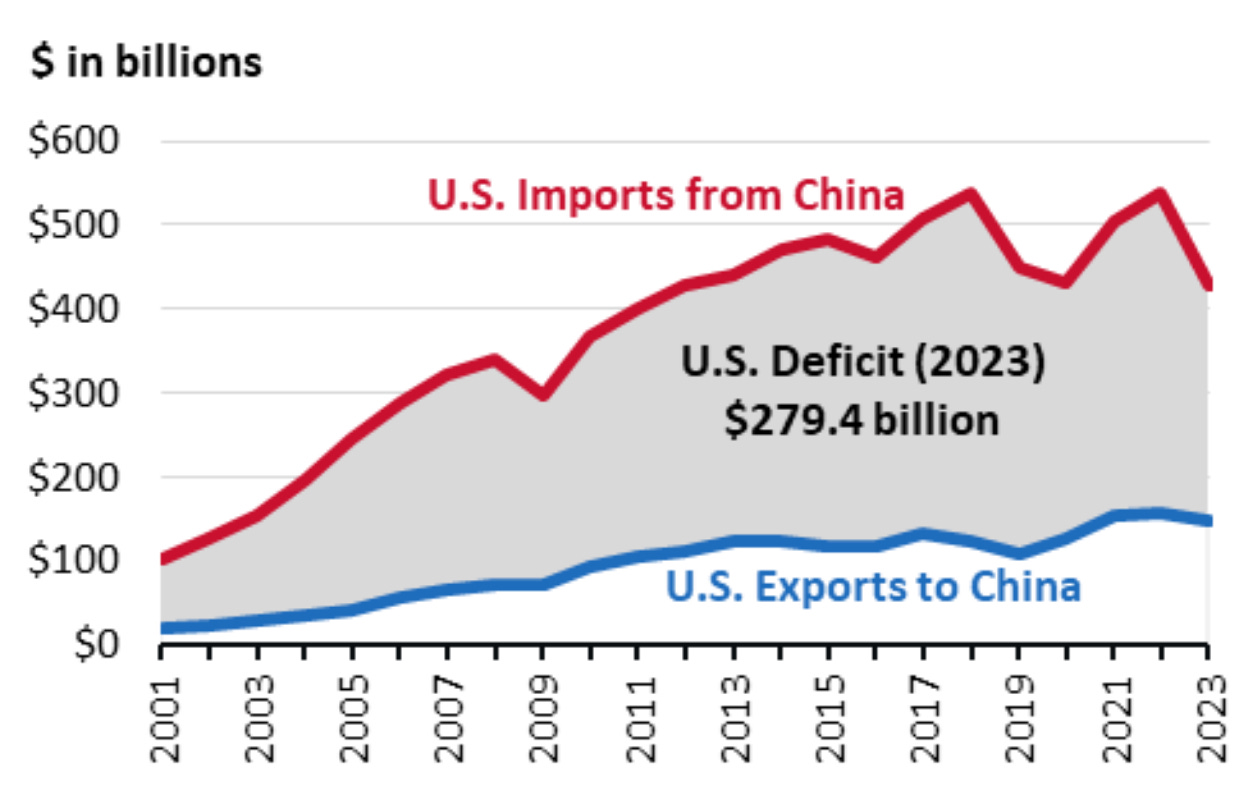

Moreover, trade between China and Western countries has steadily increased over the years, further strengthening economic ties. Despite tensions, China remains a key trading partner for the U.S. and Europe, with exports from China to the U.S. surpassing $575 billion in 202316, reflecting the enduring importance of this relationship for global commerce .

Geopolitical and Economic Risks

Despite the vast opportunities, China’s intertwined relationship with the global economy introduces risks, particularly in the realm of geopolitics. Trade tensions between China and the U.S., for example, have already led to tariffs and sanctions that have disrupted markets and forced businesses to reevaluate supply chains.

For level-headed investors, the fluid and highly competitive nature of the market, combined with government intervention, and the geopolitical tensions are key factors to monitor and consider when investing in Chinese companies as much as in Western companies with substantial business in China. As such, China demands an informed and adaptable approach for those willing to navigate its complexities.

Regulations in China

China’s regulatory environment has undergone significant changes in recent years, starting in late 2020 and intensifying in 2021, as the government sought to manage rapid economic growth, maintain social stability, and ensure long-term financial sustainability. For many Western investors, these developments have been both surprising and unsettling, especially in sectors like technology, education, and finance. Understanding these regulatory shifts is crucial to navigating China’s markets and unlocking the broader potential of its economy.

While there are many individuals more qualified than I am to discuss China in detail, I aim to provide a concise summary of these regulations, their implications for society and the economy, and offer my perspective on the stock market’s overreaction that has led to Chinese companies being substantially discounted in the stock market for years.

Key Regulatory Developments

Financial stability (2020-2021, 2023): The Chinese government has implemented significant measures to ensure financial stability, with the restructuring of Ant Group17 being one of the most notable examples. The fintech giant was required to reorganize into a financial holding company, subjecting it to stricter regulations under the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). This move was part of broader regulatory reforms targeting fintech companies, including tighter capital requirements, enhanced risk management standards, and greater scrutiny of business practices. The establishment of the National Administration for Financial Regulation (NAFR) in May 2023 marked a major overhaul of China’s financial oversight. The NAFR now oversees various fintech operations, responsibilities that were previously managed by the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC). These actions were driven by concerns about the risks posed by the rapid growth of fintech firms to the broader financial system, with the aim of mitigating systemic risks.

Antitrust and anti-monopoly (2020, 2022, 2023): One of the primary regulatory actions taken by Chinese authorities has been the crackdown on anti-competitive practices, specifically targeting e-commerce giants like Alibaba. A key focus has been the elimination of the Two Choose One18 policy, which restricted merchants (sellers) from working with multiple platforms. This move was part of broader antitrust measures to foster fair competition, reduce monopolistic behaviors, and create a level-playing field for smaller companies. In 2023, further regulations were introduced to enhance enforcement and compliance guidelines, particularly focusing on the platform economy and industries critical to public welfare.

Data privacy and protection (2021, 2023): With the rapid digitalization of the economy, China introduced the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in November 2021, mirroring global data privacy laws like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This law regulates how companies collect, store, and process personal data, reflecting a global trend toward tighter data security. In 2023, the Data Security Law (DSL) and Cybersecurity Law (CSL) added further requirements, particularly for cross-border data transfers, requiring government assessments, Standard Contract Clauses (SCCs), or Personal Information Protection Certifications (PI Certifications). Enforcement also ramped up, with regulators targeting data collection practices in mobile apps, ensuring stricter compliance. Given the sensitive nature of data and its growing strategic importance, this law and its recent adjustments mark a critical step in China’s broader regulatory push.

Education sector (2021, 2024): In one of its most dramatic regulatory moves, China’s government targeted the after-school tutoring sector, mandating that companies in the compulsory education space transition to nonprofit organizations. This policy aimed to ease the financial burden on families and promote educational equity by making tutoring more accessible. The impact on for-profit tutoring institutions has been substantial. In February 2024, new draft regulations were introduced to further strengthen oversight of the after-school tutoring industry, outlining clearer requirements for licensing, scheduling, pricing, and penalties for non-compliance.

Common Prosperity initiative (2021-2023): Income inequality has become a growing concern for the Chinese government, leading to the announcement of the Common Prosperity initiative. This initiative underscores the government’s intent to address income inequality and promote social equity. This initiative has reshaped the operational landscape for Chinese companies by pushing them to contribute more to society, redistribute wealth, and align with national goals. While this has created new challenges, especially for technology giants and private companies, it also presents opportunities for businesses to demonstrate their alignment with government priorities and to enhance their social impact.

Gig economy reforms (2021-2023): These reforms aim to improve working conditions for millions of workers in sectors like food delivery and ride-hailing. Key changes include requiring companies like Meituan19 (food delivery) and Didi20 (ride-hailing) to provide fair pay, accident insurance, and safer working conditions to gig workers. These reforms are similar to those discussed and sometimes implemented in other regions of the world.

Pessimism and Panic: Misreading China’s Moves

Prior to the regulatory measures, Chinese stocks were performing well, with major indices like the CSI 300 index and the Hang Seng index reaching multi-year highs. In February 2021, technology giants like Alibaba and Tencent were trading at strong valuations, boosted by China’s rapid post COVID-19 recovery and growing global interest in Chinese technology businesses.

By late 2021, as China’s internet giants lost more than $1 trillion combined in market capitalization from their February 2021 peak, a sense of pessimism spread across the investor landscape. This panic began with Jack Ma’s, Alibaba founder, speech at a conference in November 2020, where he criticized China’s financial regulatory framework, shortly followed by the halting of Ant Group’s record-breaking IPO.

Education stocks lost more than 90% of their value after the government’s regulatory moves. The CSI 300 and Hang Seng indexes plunged by more than 40% from their peak in February 2021 to their trough in October 2022.

Many investors, financial analysts and market commentators feared that China’s leadership was abandoning market-driven reforms and turning its back on foreign capital. The government’s escalating interventions in various sectors, from technology and finance to education, further fueled these anxieties.

Pessimism often misses the bigger picture.

Regulations have been tightening, but where is this not happening globally? In China’s case, these regulatory moves are part of a broader strategy aimed at curbing monopolistic practices, ensuring financial stability, and promoting common prosperity. China’s long-term trajectory is still focused on upward growth, and these regulatory adjustments may ultimately be beneficial, both socially and economically. As a level-headed investor navigating the complexities of China’s regulatory landscape, it’s critical to acknowledge both the risks and the opportunities.

September 2024: China Unveils Significant Stimulus to Boost Economy

On September 24th, 2024 China unveiled a comprehensive set of regulatory and stimulus measures aimed at revitalizing its struggling economy, which has been grappling with deflationary pressures, high youth unemployment, and a prolonged property market downturn. In stark contrast to Western economies, which continue to wrestle with inflation, China’s challenges lie in stimulating demand and counteracting deflation. This divergence underscores the complexity of the global economic landscape, where China faces issues of slowing growth and falling prices, while Western countries focus on containing rising costs and inflationary pressures.

The enacted measures span across monetary easing, real estate support, and capital market enhancements, all designed to steer the economy back on track toward its 2024 GDP growth target of around 5%.

Below are the highlights from the announcement made by Pan Gongsheng, governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), China’s central bank and top financial regulator:

Monetary policy adjustments: The PBOC announced a reduction of 0.5% in the amount of cash that banks must hold as reserves, called Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR), freeing up approximately $142 billion in liquidity for loans. Additionally, the central bank reduced the seven-day reverse repo rate from 1.7% to 1.5%, a move aimed at stimulating the economy by reducing borrowing costs and improving access to credit. This move is expected to guide lower loan and deposit rates, maintaining stability in commercial banks’ net interest margins. Some might argue that the former of this measures, although relatively small in the grand scheme of things of the Chinese financial sector, is to counteract the negative impact that measures enacted between 2020 and 2021 have had on the financial sector. I think that freeing up capital from banks’ reserve is a sign that the Chinese government has restored its confidence in the country’s banks and believes that such capital can be put to best use to stimulate the economy.

Liquidity support for companies: A new swap program allows companies in the securities, funds, and insurance sectors to use assets as collateral to access liquidity, with an initial value of 500 billion yuan ($71 billion) and a potential ceiling of 1.5 trillion yuan, enhancing their ability to acquire funds. Additionally, a re-lending facility will guide banks in providing loans with a 2.25% interest rate to listed companies for stock buybacks, further supporting corporate stability and increasing companies’ shareholders equity. This measure is in stark contrast with the belief of market commentators and pessimists that the Chinese government is against returning value to shareholders.

The government is also considering a capital injection of up to 1 trillion yuan into its six major commercial banks, a move not seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

Overall, these stimulus efforts reflect China’s commitment to stabilizing its economy and rebuilding investor confidence by addressing financial, real estate, and corporate challenges head-on.

Navigating Regulatory Changes for Sustainable Growth

Chinese regulators, like their Western counterparts, focus on addressing issues such as wealth redistribution, gig workers protections, data privacy, and income inequality. These shared concerns highlight the similarities in regulatory priorities globally. However, China’s centralized system allows for swift regulatory action, while Western governments are often slower to implement changes due to political checks and balances. For many Western observers, the surge in Chinese regulations may appear to be a retreat from market reforms, but in reality, these regulations are designed to address societal concerns and create long-term economic stability.

While certain industries, like education, have faced severe impacts, the intent behind these measures is to ensure sustainability and fair competition, not to stifle growth or impair the country’s best businesses. China remains on track to become the world’s largest economy, with entrepreneurial energy still strong. The key is understanding which companies are best positioned to navigate this evolving landscape and which sectors might continue facing headwinds. Ultimately, these reforms, although challenging in the short term, aim to foster a more resilient and equitable economic environment, offering opportunities for those who are willing to take a long-term view.

Why Chinese Companies May Offer Strong Returns Today

Chinese stocks across different stock markets have experienced a dramatic downturn in recent years, leading some financial analysts, investors and market commentators to conclude that investing in China today is unwise. I disagree. This perspective is primarily based on past stock performance rather than current conditions. Whether investing in Chinese equities is still a poor decision today is an entirely different question. Markets in China have experienced a period of heavy pessimism, but this often creates ideal buying opportunities. Warren Buffett famously advises to:

“Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.”

This encapsulates the current environment in China, where widespread fear and pessimism have driven valuations to levels that could provide significant upside for the level-headed investor. In fact, current stock market conditions suggest that participants have overreacted: share prices have fallen significantly, yet Chinese businesses are improving efficiency, increasing returns to shareholders (through aggressive buyback programs, growing cash flows or a combination of both) and have spent years adapting to a stricter regulatory environment. The earnings power of prominent Chinese companies remains robust, and the wide gap between their intrinsic value and their stock prices mirrors the opportunities seen during the 2007-2008 financial crisis in the U.S., with many Chinese stocks now available at substantial discounted prices.

In my opinion, it’s prudent to limit exposure to Chinese stocks due to geopolitical risks and demand a substantial margin of safety when purchasing Chinese stocks. However, avoiding China entirely could mean missing out on significant long-term opportunities. As Charlie Munger vividly expressed in an interview, such risks should not overshadow the potential rewards of investing in China:

“My position in China has been that: (1) the Chinese economy has better future prospects over the next 20 years than almost any other big economy. That’s number one. (2) The leading companies of China are stronger and better than practically any other leading companies anywhere, and they’re available at a much cheaper price.

So naturally, I’m willing to have some China risk in the Munger portfolio. How much China risk? Well, that’s not a scientific subject, but I don’t mind whatever it is 18% or something.”

Seizing Opportunities in China

Investing in China has been a humbling journey filled with invaluable lessons. Years ago, I recognized my limited understanding of the complexities posed by China’s intense competition and the government’s frequent, decisive interventions in corporate affairs. Still, I wanted exposure to a rapidly growing and prominent Asian economy, so I chose to delegate my Chinese investment decisions to an Investment Trust21, JPMorgan China Growth & Income, allocating a small portion of my capital to it for about two years. This allowed me to observe China’s market dynamics and learn more about its economy without fully committing. Eventually, in March 2024, I decided to sell out and dive into independent research.

Since then, I’ve closely followed the further developments of regulations to deepen my understanding of the country’s economy and their impact on companies. I’ve also taken a closer look at prominent Chinese businesses, waiting for the right opportunity to establish a sizeable position. In late August 2024, following the company’s second quarter 2024 results, I initiated a position in Pinduoduo (PDD 0.00%↑) at what I believe to be a substantial discount to its intrinsic value: the market overreaction to the company’s quarterly earnings report and its outlook for the rest of the year resulted in a significant pullback of around 39%, which I saw as an opportunity to purchase a great business at a steep discount.

The stock market in China reacted positively to the September 24th, 2024 government’s announcement of new financial stimulus measures, triggering a strong rally across various indices. Many Chinese stocks continued to climb into this week. However, I don’t base my investment decisions on market sentiment. I had already allocated capital to Pinduoduo during a period of significant negativity towards Chinese stocks. Despite the stock appreciating over 60% since my investment in August, I don’t intend to add more just because other investors have become optimistic. Instead, I will continue to closely monitor the company’s progress. I may consider allocating more capital if my conviction in the business fundamentals and future prospects strengthens, and if I determine there is a significant gap between its intrinsic value and the market price. With Chinese stocks being rapidly repriced, there’s a possibility that future returns will be compressed.

While my Western investment experience provided limited insight into China’s distinct market dynamics, this evolving landscape has provided a remarkable learning opportunity. China’s vast entrepreneurial spirit and its inevitable rise to become the world’s largest economy offer both challenges and significant opportunities. I remain committed to exploring these prospects, confident that each investment not only presents financial potential but also broadens my understanding of this dynamic market in a fascinating country.

Conclusion

Is investing in China worth the risk? In my view, the answer is a resounding yes.

China is a land of contrasts, where ancient history meets cutting-edge innovation, and a single-party state coexists with thriving enterprise. As a level-headed investor, the opportunities are immense, but they come with unique challenges that require thoughtful navigation. My approach remains grounded in the core principles of value investing, recognizing both the risks and the potential rewards without overemphasizing one at the expense of the other.

It’s essential to acknowledge that the risks in China are real. The country’s rapid transformation, distinct governance model, and dynamic market environment provide fertile ground for those willing to adapt and learn. Moreover, the economic interdependency between China and the West grows each year: China is deeply embedded in the global manufacturing and technological supply chain. Any significant disruption would reverberate far beyond China’s borders. The risk of investing in China is not limited to companies based there; Western businesses are also deeply intertwined with China’s economy.

With sentiment toward China near rock bottom, this presents an ideal opportunity: high-quality Chinese companies are trading at significantly lower multiples compared to their Western counterparts, despite their great track record in recent years and strong growth prospects for years to come.

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether the risks exist but whether the potential rewards justify them. For those willing to take the long view, the answer is yes.

Economic Reform in China: Current Progress and Future Prospects by China Briefing

World Economic Outlook database

According to World Bank estimates, more than 800 million people in China have been lifted out of extreme poverty since the 1980s. This reduction in poverty is widely regarded as one of the most significant achievements in modern development.

Reference: The World Bank In China.

A Special Economic Zone (SEZ) is a designated geographical area within China where business and trade laws are different from the rest of the country. These zones are established to encourage economic growth, attract foreign investment, increase trade, and boost job creation by offering more liberal economic policies, such as tax incentives, reduced tariffs, and less stringent regulations. China’s first SEZ, established in Shenzhen in 1980, is one of the most notable examples.

China Population by WorldOMeters.

Shein, founded in 2008, is a Chinese fast-fashion retailer that has reshaped online shopping with its data-driven approach, innovative supply chain, and direct-to-consumer business model. Shein uses the Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M) model to produce low-cost fashion quickly based on real-time consumer demand. It has gained a significant global following and challenged more established players in the fashion industry.

Pinduoduo, founded in 2015, pioneered the group purchase model, where consumers band together to get discounts directly from manufacturers. This model falls under social commerce, and Pinduoduo’s approach is notable for being highly interactive and social, often involving gaming elements.

Alibaba, founded in 1999 by Jack Ma, is a conglomerate specializing in e-commerce, technology, and retail. The company operates a variety of businesses including Alibaba.com, a business-to-business platform, Taobao for consumer-to-consumer transactions, and Tmall, focused on business-to-consumer sales. Alibaba has grown into one of the largest e-commerce companies globally, playing a pivotal role in shaping online retail in China and internationally.

JD.com, founded in 1998, is a major e-commerce company. Initially focused on selling electronics, it has since expanded to offer a wide range of products, including apparel, groceries, and luxury goods. JD.com distinguishes itself with its extensive logistics network, including its own delivery service, which ensures faster and more reliable shipping.

Tencent, founded in 1998 by Ma Huateng, through its social platform WeChat and gaming empire, was indeed a pioneer in monetizing virtual goods, well before many Western companies adopted similar models. The company’s early move into freemium models, where users can play games for free but purchase in-game items, was highly successful and became a standard in the gaming industry globally. Tencent’s approach to social commerce and in-game purchases has been emulated by global competitors.

Huawei, founded in 1987, is a technology company. It specializes in telecommunications equipment, smartphones, and 5G technology, making it a leader in network infrastructure and innovation.

BYD (Build Your Dreams), founded in 1995 by Wang Chuanfu, is a leading manufacturer of electric vehicles (EVs) and rechargeable batteries, playing a major role in the global transition to green energy. BYD has diversified its business to include cars, buses, trucks, and renewable energy solutions, making it one of the top electric vehicle manufacturers worldwide.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), founded in 1987, is the world’s largest dedicated independent semiconductor foundry. Based in Taiwan, TSMC plays a critical role in global technology by producing advanced microchips for leading tech companies, including Apple, Nvidia, and Qualcomm.

How Important Is China for Apple? by Statista.

U.S.-China Trade Relations by United States Congressional Research Service.

Ant Group is a fintech company that originated as the financial arm of Alibaba. It operates Alipay, one of the largest mobile and online payment platforms globally. Ant Group has expanded its services to include wealth management, insurance, loans, and credit scoring, making it a major player in China’s fintech sector.

Meituan, founded in 2021, is a service platform that specializes in local services such as food delivery, hotel booking, and ride-hailing. Meituan is one of the largest on-demand service platforms in China, connecting consumers with various local merchants through its app. It has grown rapidly, becoming a key player in the food delivery and e-commerce service industries in China.

Didi, founded in 2012, is a ride-hailing company. It operates a mobile platform for transportation services, including taxis, private cars, and bike-sharing. Didi is one of the largest ride-hailing services in the world, offering services similar to Uber, and has expanded to several international markets. The company plays a significant role in China’s urban mobility, leveraging technology for convenience in transportation.

An Investment Trust is a publicly traded company that pools money from investors to create a diversified portfolio of assets. It operates as a closed-end fund with a fixed number of shares that are bought and sold on the stock exchange. Managed by professional fund managers, investment trusts can use borrowing (gearing) to potentially enhance returns, but this also increases risk.